Lessons for implementing co-stewardship

This article has reported on emerging insights from our case study research. Further case studies are planned, and more in-depth research with residents is also yet to take place. Nonetheless, across the three cases, a number of important lessons about how to engage communities as co-stewards have started to emerge.

Lesson 1: Recognise existing community engagement with water and tailor strategies accordingly

The case studies illustrate the importance of first understanding how communities are already engaging with sustainable water management before introducing new approaches.

Community engagement programmes often start by assuming that communities aren’t engaging with water and that such engagement thus needs to be instigated. Instead, our case studies have shown that communities are often already actively working by themselves to bring about more sustainable water management.

In Project Zero it was critical to recognise the existing water efficiency measures many households were already undertaking. In Project Groundwater it was vital to be informed by and responsive to existing community action rather than adopting a onesize-fits-all approach to engagement. Recognising and building upon existing community practices is a critical aspect of effective co-stewardship.

Starting from a position of mutual respect helps to facilitate a more trusting and collaborative relationship that can encourage communities to take an even more active role in managing water sustainably.

Lesson 2: Value community expertise and actively incorporate their input

A second key lesson from our cases is the emphasis on valuing community expertise.

In Project Groundwater, the organisers built on the work already undertaken by community flood forums rather than introducing entirely new flood mitigation measures. Similarly, in CaSTCo, collaboration with the Wensum Catchment Partnership was crucial in shaping the citizen science and community monitoring initiative allowing the community’s knowledge of point-source pollution to improve the accuracy of water quality maps and demonstrating how local expertise can enhance project outcomes.

Too often, community engagement initiatives still assume that communities suffer from a deficit of information and knowledge and need specialists to educate and inform them. Local community knowledge and expertise is assumed not to exist or is denied and ignored.

Instead, our case studies have shown the value of acknowledging existing community knowledge and action, and how working with and alongside it can act as the basis of more successful long-term relationships crucial for effective co-stewardship.

Lesson 3: Enable communities to lead in developing solutions

Across the three case studies, a recurring factor for success has been allowing communities to take the lead in shaping solutions to local water management challenges.

In Project Groundwater, the Pang Valley Flood Forum played a central role in guiding flood mitigation efforts based on their existing knowledge. Similarly, in CaSTCo, community stakeholders such as the Wensum Catchment Partnership were given the responsibility to direct citizen science initiatives.

Project Zero also demonstrated this by involving residents in water-saving pledges, letting them choose and commit to practices that best suited their circumstances.

These examples underscore the importance of not rushing in with pre-formed and inflexible solutions. Rather, developing effective co-stewardship demands engaging with communities early to ensure their concerns are properly understood and then allowing communities to actively drive the design and development of solutions to ensure they are responsive to their unique contexts.

Lesson 4: Foster honest and open dialogue through transparent sharing of information and resources

Our case studies highlight the importance of local authorities, water companies and government agencies initiating open and honest dialogue with communities and sharing information transparently. This can take several forms.

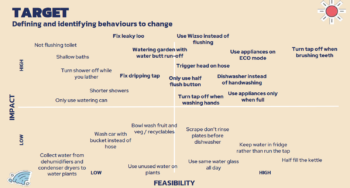

In Project Zero, planners provided communities with important contextual information about the water-saving potential of specific behaviours (e.g., how much water can be saved by taking shorter showers), enabling residents to make informed decisions about which practices to adopt.

Similarly, in CaSTCo, the Environment Agency openly shared its resource constraints with the citizen science community, explaining how their data would be used. This transparency allowed the citizen scientists to understand that the Environment Agency would struggle to act on its own and without their help.

In both of these cases, the project organisers began from a position of humility and honesty about their own limitations and constraints. Rather than presenting themselves as having all the expertise and knowing all the answers already, they actively approached communities to seek input and collaboration and then used the expertise and resources they did have to develop and support solutions based on novel forms of partnership and co-stewardship.